Net Working Capital in M&A

What is the Role of Net Working Capital in the M&A Process?

Working capital (or a company’s current assets minus its liabilities) is one of the most misunderstood concepts in corporate America and has been responsible for many transactions’ failure to close. Net working capital (also referred to as NWC or working capital) analysis is usually left to the end of most merger and acquisition (M&A) processes and is often highly contested due to the intricacies involved in this calculation. Sellers often misinterpret working capital as being measured in “months,” and representative of cash burn or some kind of safety net regarding corporate liquidity.

In reality, working capital calculations follow generally accepted formulas designed to measure a company’s cash generating capabilities along with those current assets and liabilities that impact cash conversion cycles. Working capital formulas are often customized to the transaction being contemplated, see below for some high-level examples.

Buyers calculate average working capital levels over time (often at six, nine, and 12 month intervals) to understand the impact of seasonality on cash flows and determine an appropriate working capital benchmark or “peg.” Buyers and sellers negotiate upon that target amount to ensure that the level is appropriate. Conventional wisdom dictates buyers want higher levels of working capital while sellers want lower. Regardless, once the peg is established, a “truing-up” process will happen post close with adjustments made accordingly. If the seller’s working capital is lower than the target at the closing date, the buyer will reduce the purchase price. Likewise, if the true-up determines a higher level of working capital than what was agreed to on day of close, the seller will keep the excess.

An experienced M&A advisor can help sellers navigate the negotiation process and ensure a fair and attainable working capital target. If you are exploring the sale of your business contact one of our experts to learn more about working capital in the M&A process.

Calculating Net Working Capital

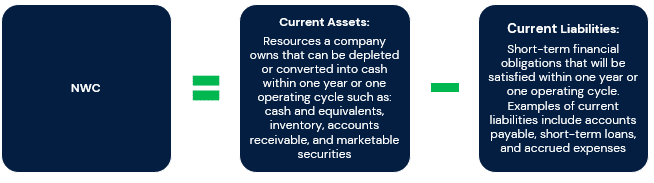

Working capital is calculated by subtracting a company’s current liabilities from its current assets and is used to measure the company’s operating liquidity and short-term financial health.

Positive working capital allows companies to fund their current operations, pay off short-term bills, and internally finance growth. If a company’s current liabilities exceed its current assets, then the company has a working capital deficit, and may have trouble paying back creditors and fostering growth. However, substantial positive working capital is not always optimal as it may indicate that the business has too much inventory or has not been investing enough of its cash. It is crucial for businesses to be mindful of working capital to remain solvent and grow sustainably.

Working Capital Cycle

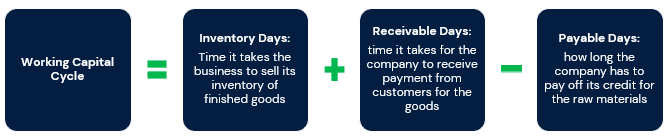

When considering a company’s working capital, it is important to know its working capital cycle, or the length of time it takes the company to convert working capital into cash. Companies that have high inventory turnover rates and receive payment from customers immediately, like grocery stores, restaurants, online retailers, and telecom companies, can remain viable while running working capital deficits.

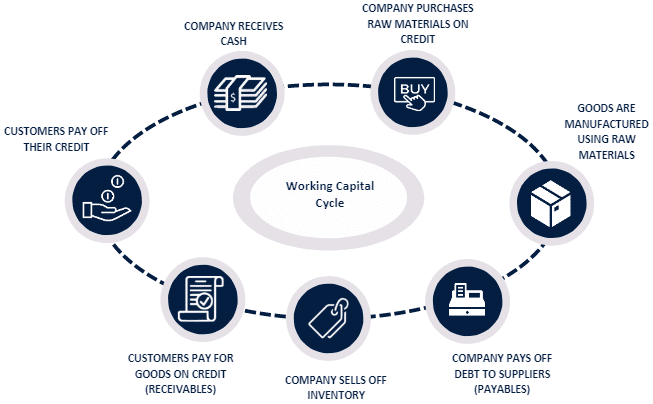

The working capital cycle, also known as the cash conversion cycle, is illustrated in the graphic below. As an effort to optimize cash flow and improve short-term liquidity condition, businesses typically aim to sell inventory and collect revenue from customers as soon as possible and pay off bills slowly.

Example 1: Positive/Normal Working Capital Cycle

Businesses with positive/normal cycles (where inventory days plus receivable days exceed payable days) often require external financing to cover the period before they receive payment from customers.

- Company X, purchases on credit and has 60 days to pay for the raw materials

- Company X, on average, sells its inventory in 55 days

- Company X receives payment from customers within 10 days

Working Capital Cycle = 55 + 10 – 60 = 5

Company X must pay out of pocket for 5 days before receiving full payment from customers.

Example 2: Negative Working Capital Cycle (Cash-Only Business)

Businesses with negative working capital cycles that quickly sell their inventory and receive payment from customers can remain solvent while running a working capital deficit.

- Company Y, purchases on credit and has 60 days to pay for the raw materials

- Company Y, on average, sells its inventory in 50 days

- Company Y receives payment from customers immediately (0 days)

Working Capital Cycle = 50 + 0 – 60 = -10

Company Y receives full payment from customers 10 days before it must pay suppliers.

Our Financial Advisory Services (FAS) group provides expert corporate financial consulting services. If you are interested in connecting with one of our professionals to discuss your company’s working capital management or have any other accounting questions, contact one of our experts.

Insights for Middle Market Leaders

Receive email updates with our proprietary data, reports, and insights as they’re published for the industries that matter to you most.